A community of 30,000 US Transcriptionist serving Medical Transcription Industry

Obama's news blackout

Posted: Jun 23, 2011

|

Why is there a Media Blackout on Nuclear Incident at Fort Calhoun in Nebraska?

By Patrick Henningsen

|

|

|

Global Research, June 23, 2011

|

|

|

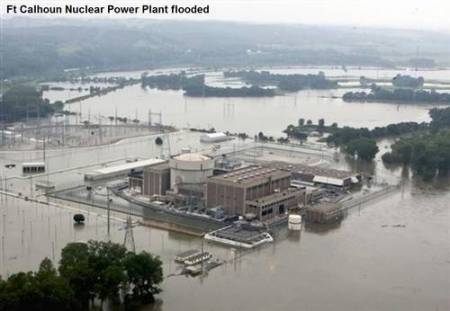

Since flooding began on June 6th, there has been a disturbingly low level of media attention given to the crisis at the Fort Calhoun Nuclear Facility near Omaha, Nebraska. But evidence strongly suggests that something very serious has in fact happened there. On June 7th, there was a fire reported at Fort Calhoun. The official story is that the fire was in an electrical switchgear room at the plant. The apparently facility lost power to a pump that cools the spent fuel rod pool, allegedly for a duration of approximately 90 minutes. FORT CALHOUN NUKE SITE: does it pose a public risk? The following sequence of events is documented on the Omaha Public Power District’s own website, stating among other things, that here was no such imminent danger with the Fort Calhoun Station spent-fuel pool, and that due to a fire in an electrical switchgear room at FCS on the morning of June 7, the plant temporarily lost power to a pump that cools the spent-fuel pool. In addition to the flooding that has occurred on the banks of the Missouri River at Fort Calhoun, the Cooper Nuclear Facility in Brownville, Nebraska may also be threatened by the rising flood waters. As was declared at Fort Calhoun on June 7th, another “Notification of Unusual Event” was declared at Cooper Nuclear Station on June 20th. This notification was issued because the Missouri River’s water level reached an alarming 42.5 feet. Apparently, Cooper Station is advising that it is unable to discharge sludge into the Missouri River due to flooding, and therefore “overtopped” its sludge pond. Not surprisingly, and completely ignored by the Mainstream Media, these two nuclear power facilities in Nebraska were designated temporary restricted NO FLY ZONES by the FAA in early June. The FAA restrictions were reportedly down to “hazards” and were ‘effectively immediately’, and ‘until further notice’. Yet, according to the NRC, there’s no cause for the public to panic. A news report from local NBC 6 on the Ft. Calhoun Power Plant and large areas of farm land flooded by the Missouri River, interviews a local farmer worried about the levees, “We need the Corps-Army Corps of Engineers–to do more. The Corps needs to tell us what to do and where to go. This is not mother nature, this is man-made.” Nearby town Council Bluffs has already implemented its own three tier warning system should residents be prepared to leave the area quickly. On June 6, 2011, the Federal Aviation Administration put into effect ‘temporary flying restrictions’–until further notice–over the Fort Calhoun Nuclear Power Plant in Blaine, Nebraska. To date, no one can confirm whether or not the Ft Calhoun Nuclear incident is at a Level 4 emergency on a US regulatory scale. A Level 4 emergency would constitute an “actual or imminent substantial core damage or melting of reactor fuel with the potential for loss of containment integrity.” According to the seven-level International Nuclear and Radiological Event Scale, a Level 4 incident requires at least one death, which has not occurred according to available reports. Nuclear engineer Arnie Gundersen explains how cooling pumps must operate continuously, even years after a plant is shut down. According a recent report on the People’sVoice website, The Ft. Calhoun plant — which stores its fuel rods at ground level according to Tom Burnett – is now partly submerged and Missouri River levels are expected to rise further before the summer if finished, local reports in and around the Fort Calhoun Nuclear Plant suggest that the waters are expected to rise at least 5 more feet. Burnett states, “Ft. Calhoun is the designated spent fuel storage facility for the entire state of Nebraska…and maybe for more than one state. Calhoun stores its spent fuel in ground-level pools which are underwater anyway – but they are open at the top. When the Missouri river pours in there, it’s going to make Fukushima look like an X-Ray.” The People’s Voice’s report explains how Ft Calhoun and Fukushima share some of the very same high-risk factors: “In 2010, Nebraska stored 840 metric tons of the highly radioactive spent fuel rods, reports the Nuclear Energy Institute. That’s one-tenth of what Illinois stores (8,440 MT), and less than Louisiana (1,210) and Minnesota (1,160). But it’s more than other flood-threatened states like Missouri (650) and Iowa (420).” Conventional wisdom about what makes for a safe location regarding nuclear power facilities was turned on its head this year following Japan’s Fukushima disaster following the earthquake and tsunami which ravaged the region and triggered one of the planets worst-ever nuclear meltdowns. As was the critical event in Fukushima, in Ft Calhoun circulating water is required at all times to keep the new fuel and more importantly the spent radioactive material cool. The Nebraska facility houses around 600,000 – 800,000 pounds of spent fuel that must be constantly cooled to prevent it from starting to boil, so the reported 90 minute gap in service should raise alarm bells. TV and radio journalist Tom Hartmann explores some of these arguments here: Nebraska’s nuclear plant’s similarities to Japan’s Fukushima, both were store houses for years of spent nuclear fuel rods. In addition to all this, there are eyewitness reports of odd military movements, including unmarked vehicles and soldiers. Should a radiation accident occur, most certainly extreme public controls would be enacted by the military, not least because this region contains some of the country’s key environmental, transportation and military assets.

Here is a video regarding the flooding experienced along the Missouri River in Nebraska:

RISK: Levees in and around Omaha were not designed for 3 months of water. Angela Tague at Business Gather reports also that the recent Midwest floods may seriously impact food and gas prices. Lost farmland may be behind the price spike to $7.55 a bushel for corn, already twice last year’s price. Tague notes also:

One of the lessons we can learn for Japan’s tragic Fukushima disaster is that the government’s choice to impose a media blackout on information around the disaster may have already cost thousands of lives. Only time will tell the scope the disaster and how many victims it will claim.

More importantly, though, is that public officials might do well to reconsider the “safe” and “green” credentials of nuclear power- arguably one of the dirtiest industries going today. Especially up for inspection are those of 40 year old facilities like Ft Calhoun in the US, strangely being re-licensed for operation past 2030. Many of these facilities serve little on the electrical production front, and are more or less “bomb factories” that produce material for nuclear weapons and depleted uranium munitions.

Perhaps ‘Fukushima’ could become an annual event for the nuclear industry.

|

|

|

|

|

Is my friend, Warren Buffett, still in town? - Henny Penny

[ In Reply To ..]Perhaps there is no story to report on.

digging - smithclar

[ In Reply To ..]Dig deeper than the mainstream. It's there.

http://www.thebulletin.org/web-edition/columnists/dawn-stover/rising-water-falling-journalism

Rising water, falling journalism

Every evening, my father climbs the levee along the Missouri River in Council Bluffs, Iowa, and peers down into the black water that swallows the road. The water is rising, and the Army Corps of Engineers says the levee has never faced such a test. Dad, a retired professor, is packing his books and papers. If the levee doesn't hold, his one-story house could be underwater for months.

A little farther up the Missouri, at the Fort Calhoun Nuclear Power Station near Blair, Nebraska, the river is already lapping at the Aqua Dams -- giant plastic tubes filled with water -- that form a stockade around the plant's buildings. The plant has become an island.

In Blair, in Council Bluffs, and in my hometown of Omaha -- which are all less than 20 miles from the Fort Calhoun Station -- some people haven't forgotten that flooding is what caused the power loss at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant and the disastrous partial meltdowns that followed. They're wondering what the floodwaters might do if they were to reach Fort Calhoun's electrical systems.

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) issued a "yellow finding" (indicating a safety significance somewhere between moderate and high) for the plant last October, after determining that the Omaha Public Power District (OPPD) "did not adequately prescribe steps to mitigate external flood conditions in the auxiliary building and intake structure" in the event of a worst-case Missouri River flood. The auxiliary building -- which surrounds the reactor building like a horseshoe flung around a stake -- is where the plant's spent-fuel pool and emergency generators are located.

OPPD has since taken corrective measures, including sealing potential floodwater-penetration points, installing emergency flood panels, and revising sandbagging procedures. It's extremely unlikely that this year's flood, no matter how historic, will turn into a worst-case scenario: That would happen only if an upstream dam were to instantaneously disintegrate. Nevertheless, in March of this year the NRC identified Fort Calhoun as one of three nuclear plants requiring the agency's highest level of oversight. In the meantime, the water continues to rise.

No guarantees. On June 7, there was a fire -- apparently unrelated to the flooding -- in an electrical switchgear room at Fort Calhoun. For about 90 minutes, the pool where spent fuel is stored had no power for cooling. OPPD reported that "offsite power remained available, as well as the emergency diesel generators if needed." But the incident was yet another reminder of the plant's potential vulnerability.

And so, Fort Calhoun remains on emergency alert because of the flood -- which is expected to worsen by early next week. On June 9, the Army Corps of Engineers announced that the Missouri River would crest at least two feet higher in Blair than previously anticipated.

The Fort Calhoun plant has never experienced a flood like this before. The plant began commercial operation in 1973, long after the construction of six huge dams -- from Fort Peck in Montana to Gavins Point in South Dakota -- that control the Missouri River flows and normally prevent major floods. But, this spring, heavy rains and high snowpack levels in Montana, northern Wyoming, and the western Dakotas have filled reservoirs to capacity, and unprecedented releases from the dams are now reaching Omaha and other cities in the Missouri River valley. Floodgates that haven't been opened in 50 years are spilling 150,000 cubic feet per second -- enough water to fill more than a hundred Olympic-size swimming pools in one minute. And Fort Calhoun isn't the only power plant affected by flooding on the Missouri: The much larger Cooper Nuclear Station in Brownville, Nebraska, sits below the Missouri's confluence with the Platte River -- which is also flooding. Workers at Cooper have constructed barriers and stockpiled fuel for the plant's three diesel generators while, like their colleagues at Fort Calhoun, they wait for the inevitable.

To be sure, there are coal-fired power plants on the river in Sioux City and Council Bluffs, Iowa -- north and south of Fort Calhoun, respectively -- that presumably could provide backup power if the nuclear plant were to lose power. Operators at the coal plants are protecting critical structures with berms and sandbags, but they can't guarantee that a levee break won't take the plants offline.

Failure of the fourth estate. Newspapers and websites all over the country have reported on the flooding and fire at Fort Calhoun, but most articles simply paraphrase and regurgitate information from the NRC and OPPD press releases, which aggregators and bloggers then, in turn, simply cut and paste. Even the Omaha World-Herald didn't send local reporters to cover the story; instead, the newspaper published an article on the recent fire written by Associated Press reporters -- based in Atlanta and Washington.

Unsurprisingly, much of the information in recent press reports has lacked context. For example:

- Virtually every article about the flooding mentions that the Fort Calhoun plant was shut down on April 9. On May 27, the Omaha World-Herald reported, "The Omaha Public Power District said its nuclear plant at Fort Calhoun, which is shut down for maintenance, is safe from flooding." The implication is that being shut down makes a plant safe. But as the ongoing crisis in Fukushima demonstrates, nuclear fuel remains hot long after a reactor is shut down. When Fort Calhoun is shut down for maintenance and refueling, only one-third of the fuel in the reactor core is removed. Besides the hot fuel remaining in the core, there is even more fuel stored in the spent-fuel pool, which is not shut down. According to a May 2011 report by Robert Alvarez at the Institute for Policy Studies, there are an estimated 1,054 assemblies of spent fuel, weighing 379 tons, at Fort Calhoun. The oldest of these assemblies are in dry-cask storage, which does not require any water or electricity for cooling. Like the dry casks at Fukushima, which survived the tsunami unscathed, the Fort Calhoun casks do not appear to be in any danger from flooding.

- Many news outlets copied this sentence from a June 6 OPPD press release announcing a low-level emergency: "According to projections from the US Army Corps of Engineers, the river level at the plant site is expected to reach 1,004 feet above mean sea level later this week, and is expected to remain above that level for more than one month." Though hardly reassuring news so far, missing from these reports (and from the original release) was the elevation of the plant itself, which turns out to be -- surprise! -- 1,004 feet. According to NRC Senior Public Affairs Officer Victor Dricks, the river yesterday was at 1,005.7 feet and is expected to crest at 1,006.4 feet. By then, the plant will be standing in more than two feet of water; luckily, the eight-foot-tall Aqua Dams should keep the water at bay. And the river is still well below the worst-imaginable scenario that OPPD is required to prepare for: a flood reaching 1,014 feet above sea level. Nevertheless, in the absence of any context, the press-release language is meaningless to any reader in the neighboring communities.

- Almost every article about the fire and power loss at Fort Calhoun has quoted an OPPD spokesman who said that a diesel-powered backup pump was "available" but not needed. None of these articles, however, told readers how much diesel fuel is stored at the plant, how many generators and batteries are on site, and how long they could keep coolant circulating through both the reactor and spent-fuel pool. For the record, there are two emergency diesel generators at Fort Calhoun. According to Dricks, there is usually enough fuel on site to provide cooling for two weeks, but currently the plant has sufficient fuel for four weeks. Of course, the average newspaper reader would never know any of that or be privy to the timeline of potential events.

- Finally, many articles have reported that the temperature in the spent-fuel pools rose 2 degrees during the recent power outage. That may not sound like much, but only a few articles told readers the actual temperature of the pool. And a 2 degree rise from, say, 210 degrees Fahrenheit to 212 degrees Fahrenheit (the boiling point for water) would be catastrophic. The pool is normally kept at about 80 degrees Fahrenheit. OPPD estimated that, in the absence of any power to circulate coolant, it would take about 88 hours before water in the pool would begin boiling.

Admittedly, it's not easy finding information about Fort Calhoun, even if you're a local reporter without a tight deadline. OPPD press releases and the company's online newsroom do not provide details about the plant's layout and components. Some of that information was available before 9/11 but was removed because of concerns about terrorism. In protecting ourselves from enemies, we have also hidden vital information from ourselves. So finding the relevant facts takes some digging and dialing, and most newsrooms today don't have that kind of manpower. That's especially true at newspapers scrambling to cover a multitude of flood impacts across the region.

A June 9 report delivered by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), "Information Needs of Communities," states that the number of full-time journalists at daily newspapers has fallen from a peak of about 56,900 in 1989 to 41,600 in 2010 -- fewer than before Watergate. As the FCC report observes:

An abundance of media outlets does not translate into an abundance of reporting. In many communities, there are now more outlets, but less local accountability reporting.

While digital technology has empowered people in many ways, the concurrent decline in local reporting has, in other cases, shifted power away from citizens to government and other powerful institutions, which can more often set the news agenda.

In the absence of in-depth professional reporting on the situation at Fort Calhoun, OPPD created a web page to respond to the flurry of rumors flying around the Internet. One rumor concerns the no-fly zone ordered by the FAA on June 6, which extends two miles around, and 3,500 feet above, the nuclear plant. Contrary to rumor, the no-fly zone has nothing to do with a radioactivity release. But OPPD's rumor-control page neglects to mention that the utility requested the zone, ostensibly because of work being done on overhead power lines but also because of undisclosed "security reasons." An OPPD spokesperson said that the utility is worried about news helicopters flying low over the plant.

Greater government and industry transparency can give citizens and reporters a better understanding of what's happening at the nation's nuclear power plants, and help prevent rumors from dominating the airwaves. Nonprofit organizations such as the Bulletin can help fill today's information gap. But local reporting ultimately relies on readers and advertisers who are willing to support it. Meanwhile, in the absence of reliable information, my dad continues his evening walks to the levee and peers into the rising water to judge for himself.

Why is this "Obama's" news blackout? He's not - even mentioned in the article.

[ In Reply To ..]Not even once. When did he seize personal control over the media?

Obama, Omaha, Osama! - See a pattern? LOL, NM

[ In Reply To ..]Fort Calhoun's nuclear reactor - Farm girl

[ In Reply To ..]CNN had a story on the reactor today.

If you do not live in Nebraska or Iowa is it any of your business?

Similar Messages:

Media Blackout On DNC Lawsuit Proves That It's May 15, 2017

I had the privilege of interviewing my newest personal hero yesterday, attorney Elizabeth Lee Beck, about her legal team’s fraud case against the Democratic National Committee. One of the many useful insights that this straight-shooting mom on fire brought to light during our conversation was her story about a time she reached out to New York Times reporter Michael Barbaro to get some help cracking through the deep, dark media blackout on this extremely important case. Barbaro had previously i ...

The Bizarre Media Blackout Of Hacked Soros Documents.Aug 27, 2016

days ago provide juicy insider details of how a fabulously rich businessman has been using his money to influence elections in Europe, underwrite an extremist group, target U.S. citizens who disagreed with him, dictate foreign policy, and try to sway a Supreme Court ruling, among other things. Pretty compelling stuff, right? Not if it involves leftist billionaire George Soros. In this case, the mainstream press couldn't care less. On Saturday, a group called DC Leaks posted more than ...

Obama's Inauguration (old News) MsgJul 30, 2012

I heard there were 40,000 people at his inauguration. The good part was only 14 missed work. ...

Here's A Link From ABC News About Obama's Sep 05, 2012

People need to wise up and see this so-called President for what he is. link ...

Economic Bad News For ObamaSep 06, 2012

The backbone of America is hurting. Will Obama "fix it" this time? http://www.breitbart.com/Big-Government/2012/09/06/Unemployment-Rate-Rises-to-8-4-Percent-in-Rural-Counties ...

More Good News About Obama...Feb 11, 2014

1827 days down, 1073 days to go until he is no longer Liar in Chief, Dictator, King, Destroyer of Democracy or whatever else he may be called. ...

Fox News: Obama Administration And CyberspaceMay 17, 2011

The Obama administration wants to work with the rest of the world on cybersecurity and freedom of individuals to access information via the internet. This is still another area where I approve very much what President Obama is working to achieve. http://www.foxnews.com/politics/2011/05/16/obama-outlines-global-plan-cyberspace/?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+foxnews%2Fpolitics+%28Internal+-+Politics+-+Text%29&utm_content=Google+Feedfetcher ...

Obama, King Of Kenya - News FlashAug 23, 2012

Yesterday's Purple Poll survey results of four key swing states shows that not only will Mitt Romney likely be our next president, but also that President Obama is very unlikely to get reelected in November. Purple Strategies, a bipartisan polling firm that specializes in tracking public opinion in the “purple” swing states, released yesterday their polling results from Colorado, Virginia, Ohio and Florida. Conventional wisdom holds that neither candidate is likely to win the W ...

Obama Administration Spied On Fox News ReporterMar 05, 2017

The Justice Department spied extensively on Fox News reporter James Rosen in 2010, collecting his telephone records, tracking his movements in and out of the State Department and seizing two days of Rosen’s personal emails, the Washington Post reported on Monday. In a chilling move sure to rile defenders of civil liberties, an FBI agent also accused Rosen of breaking anti-espionage law with behavior that—as described in the agent's own affidavit—falls well inside the bounds of tra ...

Obama Holds News Briefing Today On Benghazi (sm)May 10, 2013

BEHIND CLOSED DOORS!!!!!!!!!!!!! The Transparent Snake ...

I Love To Listen To President Obama In News ConferenceJul 18, 2014

But, we haven't had somewhat this intelligent who could actually think and speak coherently on his feet in a long time. I realize some of his points you oppose, but he is handling MH17 quite nicely. ...

The Iran Agreement. Guess Obama Didn't Read The News Yet.Apr 05, 2015

Saw a video by the Iranian Foreign Minister debunking the framework that Obama states is the real deal. I do NOT want to go on any Middle East site to see this video, so I will continue to look so those naysayers that state only warmongers don't want this deal can be appeased by TRUTH.He stated what Obama told the American people, is totally wrong, according to the agreement. He said none of iran's nuclear facilities, including the Fordow center buried under a mountain, will be cl ...

ABC News Spin Meter: Obama & His Social Security Warning, Aka Replacing CluelessJan 17, 2013

Came across this little how-Washington-works explanation of the "firemen first" tactic. Note that stopping SS checks IS definitely among Obama's options, with the desirable results of allowing all other bills to be paid without fuss and making people very angry with the party they would blame most (insert your favorite here, but his is the GOP). SPIN METER: Obama and His Social Security Warning By CALVIN WOODWARD WASHINGTON abcnews.go.com ...

Fox News' Poor-Shaming Is Easily Provable & Did Fox News Even Try To Research This?May 14, 2015

Do the Fox News junkie talking heads on "Fix News" ever listen to their own drivel? Let's review how Obama was correct about Fox at the link below. ...

Google News Page Changed My Local News LocationAug 05, 2017

Has this happened to anyone else? No offense, but I could not care less what is going on Greenwich, CT (the local news location now appearing on my news page). I tried adding my town multiple times, but it did not take. I also added Greenwich, CT, and then deleted it, but it's still there. ...

Fox News Makes News (and Cuts The Interview!Nov 26, 2012

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/11/26/fox-news-interview-guest-network-wing-republican-party_n_2192506.html This is a link to an actual Fox News clip of an interview that they cut off after 90 seconds. Now there is that good ol' freedom of speech. ...

More On Rangel. Now That The News Is Out, More News Is Out.Jul 23, 2010

Nothing like dragging your feet....this all boils down to the 2008 investigation that was started then. Guess they just completed a full investigation now. This article is 2 pages and there is video on there, too, but I could barely hear it. A House ethics subcommittee announced Thursday that it found that Rep. Charles B. Rangel violated congressional ethics rules and that it will prepare for a trial, probably beginning in September. The panel is expected to make the details of his alle ...

Good News And Bad NewsFeb 22, 2015

The CEO of Aetna Insurance has decided, after conducting a review, to raise the pay of some 5,700 of their employees to $16.00 per hour. The CEO said that many of these employees were making $13 or $14 per hour and were unable to purchase the companies health insurance for themselves or their children forcing them onto public assistance. Half a million low-wage workers will get a raise in April, when Walmart lifts hourly wages at its stores in the United States to at least $9. The raise, an ...

So Fox News Is Really Trump News? They AreAug 01, 2017

Pretty disgusting all in all. Then they retracted the entire story. Many of you were up in arms about Seth Rich, what happened to that story? Well, maybe Fox realized they would be exposed for being Trump's errand boy so he could distract the media with his, wait for it, FAKE NEWS! ...

Obama's Manning Decision: Obama's Dangerous Move Reveals Scary Take On National SecurityJan 18, 2017

The commutation of Chelsea Manning’s prison term will forever be a blot on President Obama’s legacy. Just as the pardon granted Marc Rich by President Clinton on his last day in office became a totem of the odious pay-to-play money grubbing of Bill and Hillary, l’affaire Manning will be an enduring reminder of Obama’s constant pandering to special voter groups and mindless adherence to a progressive agenda. It will also stand as testimony to President Obama’s questionable fealty to ...

Obama-Hillary Email Cover-up Gets Revealed: They Know Obama And HRC EmailedNov 02, 2016

http://conservativetribune.com/obama-hillary-email-coverup/?utm_ WikiLeaks has struck again, and this latest revelation proved that the White House, not only knew about former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s private email server, they also helped cover it up! ...

Obama-Hillary Email Cover-up Gets Revealed: They Know Obama And HRC EmailedNov 01, 2016

http://conservativetribune.com/obama-hillary-email-coverup/?utm_source=Facebook&utm_ WikiLeaks has struck again, and this latest revelation proved that the White House, not only knew about former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s private email server, they also helped cover it up! ...

Obama SKIPS Self-imposed Deadline Obama Agreed ToSep 10, 2012

Guess Obama too busy with his campaign to be bothered with the pesky little details of actually doing the Obama. White House Misses Deadline Outlining Defense Cuts By Jake Tapper | ABC OTUS News – Fri, Sep 7, 2012 White House officials today acknowledged that they had not met the deadline to outline how the president would make the defense cuts required by law to be made because of the failure of ...

Really Who Wants To See A Barack Obama/Michelle Obama Movie, Not I.Aug 26, 2016

...

Another List Of OBAMA LIES USING OBAMA'S OWN WORDS::Sep 02, 2012

This is a quite a long list. Enjoy! Please note OBAMA's words in quotes from OBAMA interviews, speeches, all freely stated nby OBAMA. ABC News year event 1995 In his memoir, Obama writes of one of the watershed moments of his racial awareness — time and again in remarkable detail. It is a story about a Life magazine article that influenced him. The report was about a black man who tried to bleach his skin white. When Obama was told no such article c ...

Better Keep The News On All DayApr 19, 2013

Your favorite station is saying there is a 3rd subject and that police stopped an Amtrak train going from Boston to CT. This kid is very dangerous. He and his brother had Facebook pages, too. I've been watching since 5 a.m. Very interesting. FBI did a fantastic job. Too badk they didn't catch the younger one. Too bad CM and his ilk was totally WRONG as usual. Will they apologize? Of course not! They;ll keep trying to find a link between these Chechyans and the right wing, but since ...

Something About Fox News Being Feb 19, 2017

investigated - Roger Ailes case? ...

Et Tu, Fox NewsFeb 16, 2017

When even the Conservative Propaganda Channel, Fox News, turns against their darling Mr. Trump, you know he's in trouble... https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fysSDYkhHlU ...

May Be Old NewsFeb 02, 2015

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/robert-reich/trans-pacific-partnership_b_6585028.html ...

So Now That Fox NewsDec 17, 2016

has confirmed the Russians hacked our election do you believe it? ...